Get a race compass! Without a compass, it seems there is a herd mentality, a tendency to go with the crowd. With a compass you’ll know why you are going with the crowd, or not.

Sailboat Racing with Greg Fisher

“Surf Nazi,” on Sailing Anarchy

Until you’re pretty experienced and sailing against really good people, just sail in pressure on the tack that is closest to the mark. You’ll do well and don’t need a race compass.

“Dog,” on Sailing Anarchy

In my opinion the compass is a secondary input. A compass only provides information for one spot on the course. More important to look around and read the wind patterns by checking the heading of boats around the course.

Since acquiring a compass several years ago, I have experienced the yin and yang expressed in the three statements above. The compass has helped me in many ways, but being too reliant on it has also hurt me. For this post, I collected the existing wisdom on the pros, cons, and techniques for using a race compass.

We have updated this post from the original version with new tips, mental math examples, and refreshed links to compass sources. Unfortunately, our favorite digital compass, the Velocitek Shift is no longer in production.

Pros and Cons of Using a Race Compass

You win sailboat races by sailing faster and less distance than your opponents. To sail less distance, you must have a good feel for the angles. Many sailors develop this feel visually over time. However, not everyone can retain this visual information in the heat of battle.

Pro: precise angles matter

A compass gives you a precise tool for the angles. Winning in One-Designs, by Dave Perry, has a great table showing the dramatic gains and losses due to wind shifts in various situations, even with small shifts. A 5° shift results gives the favored side an advantage of 12% of the lateral separation. On a 200-yard starting line, that’s a 24-yard advantage. If you sail a 5° header for one minute you will lose at least four boat lengths to a boat on the lifted tack. For a simple table of advantages, check out this article from Sailing Breezes.

Pro: quick reference tool with many uses

In the heat of battle it’s nice to simplify your life. A compass gives you a quick reference for decisions in the stressful moments, such as after starts and mark roundings. A compass helps you find marks, check the starting line, and sail the lifted tack.

Con: distraction of dubious value

Many seasoned sailors say that using a race compass is just one more excuse to keep your head in the boat. You should be looking around constantly, integrating all the data about sailing angles, wind strength, and competitors. You can train yourself to recognize slight headers and store a mental picture of the average wind direction in your head. When a permanent shift occurs, your previous compass data on average wind is useless.

The verdict

I’ll go with Greg Fisher on this one: use a compass, but learn to use it as one input, and keep your head out of the boat. This is what we should strive for. The compass has helped me even on small lakes. As the lake gets bigger, a compass becomes more important, since there are fewer shore references.

Using a Race Compass: The Numbers

So, you’ve decided to try using a race compass. To use it effectively, you need to “know the numbers.” Use part of your pre-race routine to gather the data and do the math.

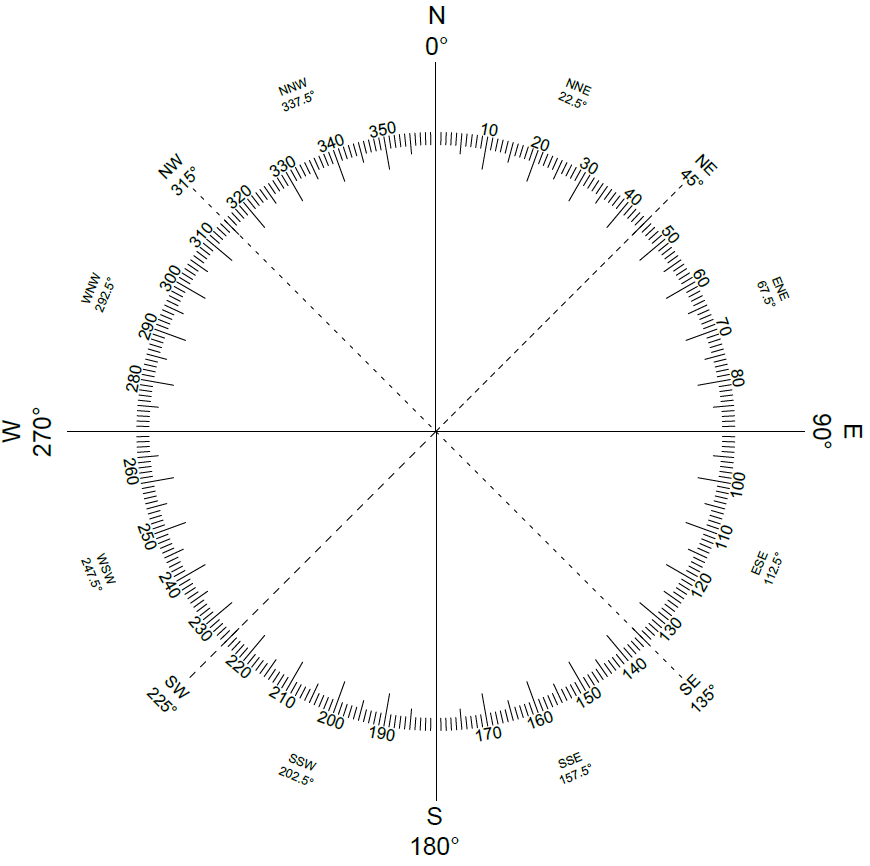

Average headings and wind direction

- Sail on each tack for at least ten minutes. The more time and more portions of the course, the better. Write down or mentally note your headings on each tack. Caution: when noting a heading, make sure you are trimmed in and sailing a true close-hauled course. If you are pinching or footing, your numbers won’t be accurate.

- Determine the average heading on each tack, and the highest and lowest values as well. Record or remember these numbers.

- Determine the average wind direction. This is the value halfway between the average heading on each tack.

Example: 235° average on port, 145° average on starboard. Average wind is 190°.

(235-145 = 90. 1/2 of 90 = 45. 45 + 145 = 190) - Check the average wind direction against other known quantities:

-Go head to wind several times and compare the compass bearing to your calculated average wind.

-Check the calculated average wind against the RC radio chatter or posted course bearing.

-Check the average wind against the forecasted direction. - Keep checking the average wind to detect any oscillations or persistent shifts that may be occurring before the start.

Tacking angle

Your tacking angle is the difference of the average readings on each tack. In the example above, the tacking angle is 90°. This is a common tacking angle in medium breeze. Tacking angles might range from 80° in slightly heavier air to as much as 100-110° in light air. As your tacking angle changes, it will affect your average headings on each tack. It’s very important to know your tacking angle in various wind ranges, even if you don’t use a compass.

Starting line bias

With shifty winds, any momentary advantage at one end of the line disappears when the wind shifts. The best strategy is to know the line bias to the average wind direction. Race Committees try to set the line square to the average wind, but they often fail.

Don’t use the windward mark placement to determine the average wind. Race committees don’t often center the windward mark on the course. See our post on ladder rungs for more about why windward mark placement doesn’t matter.

Finding line bias

Sail down the line in either direction, lining up bow and stern with the line flags or buoys. Compare the bearing to a square line. A square line will be the average wind minus 90° when sailing on starboard, or the average wind plus 90° when sailing on port.

Example: Your compass bearing when sailing the line on starboard toward the pin is 85°. The average wind is 190°. These figures give you the following insights:

- A square line bearing on starboard tack would be 190 – 90 = 100°

- The 85° bearing on starboard indicates the pin (left) end is 15° low (100 – 85).

Anything more than a 5° bias may be significant, especially if the line is long.

Memory and visualization aids for line bias

- Square line bearing on port equals the average wind plus 90 (p is for port and plus). Starboard is minus 90.

- When sailing the actual line on starboard tack, if heading is higher than the square line bearing, the left-hand side of the line is favored. If heading is lower, the right-hand side is favored. (SLR – starboard-lower-right).

- A quick way to check this without math is to sail from one end of the line at the heading you determined for the square line. Then see which end of the line is low. This doesn’t give you the actual line bearing, but may be all you need to know.

Mental math examples to try

Here are some examples. Try to do these in your head and fill in the blanks.

Example 1

- Average upwind headings: starboard tack – 060°; port tack – 140°

- Average wind direction: ________

- Tacking angle: ________

- Square line bearing on port: ________

- Square line bearing on starboard: ________

- Actual line bearing is 020° when sailing on starboard.

- Favored end (right or left): ________

- Degrees favored: ________

Click here for answer.

Example 2

- Average wind direction: 330° (You weren’t able to sail the course to get average headings, but have determined this by going head to wind several times.)

- Tacking angle: 90°

- Average upwind headings

- Starboard tack: ________

- Port tack: ________

- Square line bearing on port: ________

- Square line bearing on starboard: ________

- Actual line bearing is 260° when sailing on starboard.

- Favored end (right or left): ________

- Degrees favored: ________

Click here for answer.

Mental math overload?

If you don’t want to do all the mental math, there are options. Some digital compasses can record the average headings on each tack and show relative lifts and headers. Analog race compasses have lubber lines and other accessories to help you do the math. There is also the Tacking Master, which is an adjustable wrist dial showing all the key reference points.

Interpreting Changes – Puffs, Lulls, Lifts, Headers

As your compass heading changes while sailing upwind, it’s important to distinguish between a wind shift (lift or header) and a velocity change (puff or lull). Check your ability to interpret compass readings with these examples.

Sail luffs #1

With a nominal wind of 8 mph at 360°, you are sailing close-hauled on starboard, heading 315°. The sail begins to luff slightly. The shroud telltales begin to point further aft. The wind speed on your face feels unchanged. You bear off 5° and the boat livens up again. This is a header. You were correct in bearing off to keep the boat in the groove.

Sail luffs #2

With a nominal wind of 8 mph at 360°, you are sailing close-hauled on starboard, heading 315°. The sail begins to luff slightly. The shroud telltales begin to point further aft. The wind speed on your face feels diminished. If you bear off, the boat doesn’t react much. This is a lull, not a change in true wind direction. The boat will slow down due to reduced wind velocity and your tacking angle will increase, so you will eventually need to bear off if it lasts, but you shouldn’t bear off right away. Sailing lulls properly is not intuitive to many sailors. See our posts – Sailing Lull Tips and Sailing Lulls Tips – Part II – for more.

Strong Puff

With a nominal wind of 8 mph at 360°, you are sailing close-hauled on port, heading 45°. You see a strong puff (perhaps 12 mph) approaching on the water. As the puff hits, you ease the sheet to accelerate, but you find that you can’t steer up with the increased speed and your close-hauled heading does not change. This puff is also a header. The tacking angle decreased as you increased speed during the puff, so you should be able to head up. Since you can’t head up, the true wind direction must also have changed.

Upwind: When to Use (and When to Ignore) Your Race Compass

Getting the numbers and interpreting changes are only the first steps. The hard part is using your compass data with all the other information, including your observations of the wind, your competitors, your overall strategy, and your predictions about what will happen next. Here are some thoughts from the experts on how to solve the puzzle in various scenarios.

Oscillating breeze

In an oscillating breeze, with minimal changes in wind velocity across the course, you can simply sail the lifted tack, tacking when headed below the average heading. Waiting until you are headed below the average is very powerful. Many sailors tack at the first indication of a header and others follow. This is the herd mentality discussed in the first quote at the top of the article. For more on sailing in an oscillating breeze, see our post on Sail the Lifted Tack – How and When?

Persistent shift

In a persistent shift, you must sail toward the direction of the shift. You may have to sail a header to get there. However, it’s better to take the header early, rather than later, when the wind has shifted even further. So, in a persistent shift, ignore your compass and sail toward the shift until you are closer than your competitors (but not past the layline).

Hybrid

Most race courses are a combination of oscillating and persistent shifts, with variations in velocity across the course. The strategy here is to connect the dots and sail conservatively. Here are some tips for using the compass in these conditions.

Connect the dots

The overall strategy for hybrid conditions is to “connect the dots.” This means finding the breeze and then sailing the lifted tack. Work your way up the course by sailing toward the next shift or puff. In this scenario, you may have to take some headers to get in the breeze. Just don’t sail a big header for too long unless you’re certain it will pay off. See our post on Upwind Strategy: Connecting the Dots for more.

Don’t get too far to one side

If you get too far to one side, you will lose a lot in an unfavorable shift. On big water, use your compass to help you from getting too far to one side. When sailing away from the center, tack back on smaller headers. When sailing toward the center, only tack back to the sides on larger headers. See our post on Race with Consistency – Ted Keller Comments for more.

Sail to the advantage, but not all at once

As the race develops, various areas of the course will become advantaged. You can sail to these areas by footing, pinching, or taking slight headers to get there. Let’s say you are sailing a long lift, but see boats behind and to windward that are beginning to lift above you. Unless you see more wind ahead, you probably want to take a hitch to windward. One way to use your compass is to tack when you are on the least lifted heading. Then tack back when you reach the new wind or get a header.

If you have to go a longer distance toward an advantage, try doing it in stages, taking headers when least costly, and tacking back when you are too far headed.

Noise

In flat water with stable winds and minimal steering, a 5° shift will be noticeable and possibly worth tacking on. With difficult conditions, such as waves or highly variable wind, your compass readings will show a lot of noise, and you may not want to act unless the shift is 10° or more.

Downwind

Bearing to leeward mark

Determine the bearing from the windward mark to the leeward mark before the race starts. If you can head down to the leeward mark bearing as soon as possible after rounding, you’ll sail the least distance.

To get this number, add or subtract 180° to/from the bearing from the start to the windward mark. Example: Bearing from start to windward mark is 75°. Bearing to the leeward mark will be 255° (75 +180=255)

Sail the headed gybe

The rule of thumb for downwind sailing is to sail the headed gybe. The headed gybe is the gybe that takes you closest to the leeward mark when sailing at your preferred angle to the wind. This usually easy to see visually without a compass. On longer courses, you can use your compass bearing to sniff this out more quickly.

Get approximate average wind direction

Sailing downwind, you can also get an approximate average wind direction. This might come in handy if you don’t have much time before the race and are sailing down to the starting line. To make this work, you must be able to judge when you are sailing dead downwind. A mast-head fly is much better for this than shroud telltales, but in either case, you should test on both gybes if accuracy is important.

Permanent shift

If a permanent shift occurs, you need to adjust your numbers for average wind and heading on each tack. Sailors that focus on the race compass and the old numbers will lose big after a permanent shift. Two ways to do this:

- Watch your upwind headings on each tack and try to determine a new average.

- On the downwind leg, try to determine the new average by sailing dead downwind for a few moments.

Pre-Race Routine – Get a Leg up on the Competition – shows a detailed pre-race routine including compass use; input from Roble/Shea Sailing.