For a useful understanding of the inner workings of the wind, check out Frank Bethwaite’s Higher Performance Sailing. In Chapter 4, “The Spectrum of the Wind,” he names and describes four distinct types of wind changes we see on the race course. Understanding these changes may give you some perspective when observing the wind and deciding where to go. In this post, we’ll summarize the key points and how you might apply them.

Bethwaite has great credibility on this topic. He was meteorological coach for the Australian Olympic Yachting Team in 1972. His knowledge of quick gust peaks inspired the “automatic rigs” for the 29er and 49er skiffs. He coached Olympic skiff sailors on downwind strategies to use surges and fades.

The Spectrum of the Wind

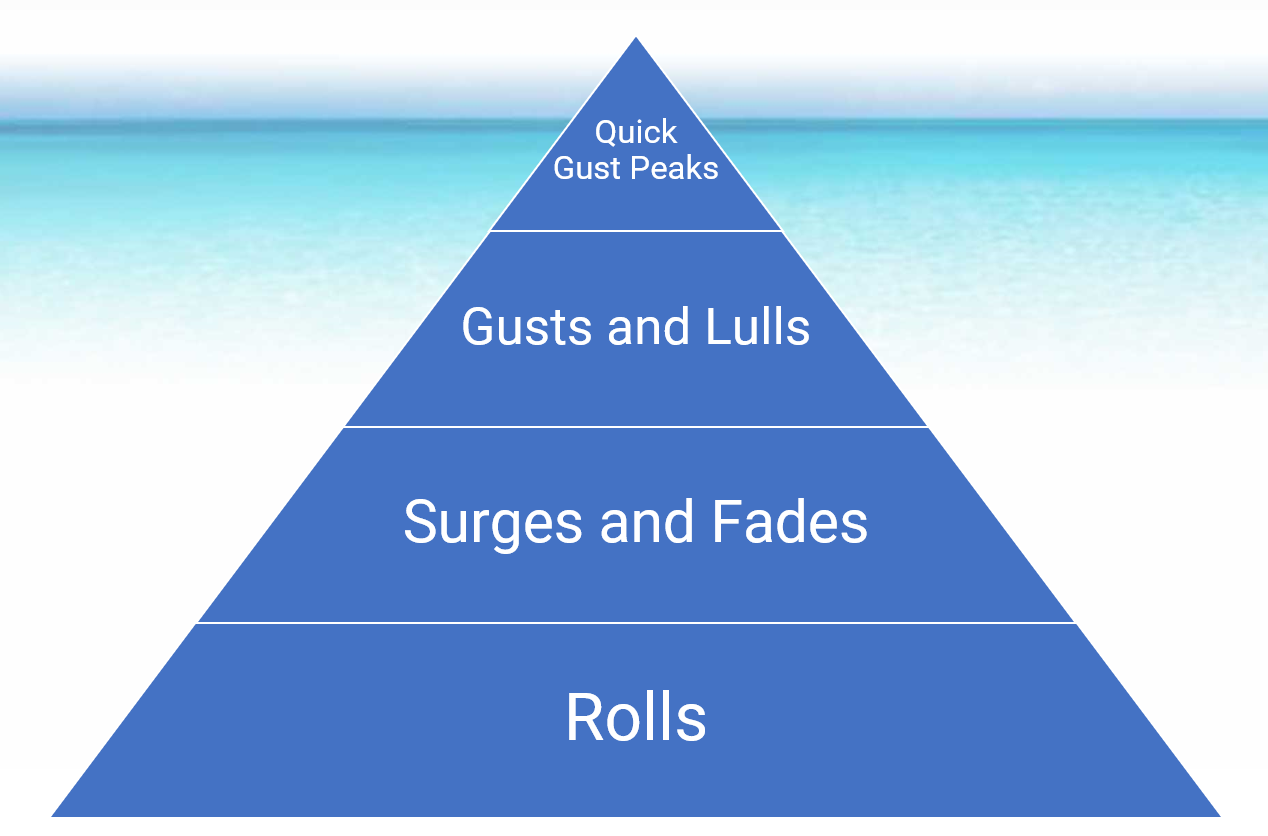

Bethwaite’s “spectrum” refers to four major types of variations in wind during a typical race. These are easy enough to understand without complex theory. His terms for them may not be familiar, but they all match our experience:

- Quick gust peaks – short peaks in wind speed not necessarily visible on the water

- Gusts (puffs) and lulls – localized areas of stronger wind interspersed within the average wind

- Surges and fades – larger areas of stronger wind (surges) and lesser wind (fades). These are not the same as large gusts.

- Rolls – still larger “wave trains” in the turbulent layer that cause regular changes in direction and increases/decreases in velocity

The key to using these variations is knowing their size, how they move, and how often they occur.

Quick Gust Peaks

Did you know that the wind speed increases and decreases rapidly by an average of +/- 7% every 6 to 12 seconds? Bethwaite identified these “peaks” by reviewing reams of traces from sensitive anemometers. His data shows they occur even in lake breezes, which are typically thought to be smooth, steady winds.

There’s not much you can do about these quick changes. They’re not necessarily associated with visible large gusts. Even if you could see them, you wouldn’t be able to adjust sail trim quickly enough to react.

Well-designed “automatic rigs” with flexible top masts can react by flexing quickly to flatten the upper sail in the peaks and returning to a fuller shape in the lulls. Bethwaite designed the automatic rigs in the 29er and 49er skiffs specifically to deal with these quick peaks.

Gusts and Lulls

Gusts are localized areas of stronger wind, caused by downdrafts due to turbulence. Lulls are recent gusts that have been slowed by surface friction to the gradient wind speed. Bethwaite says that at any time, the water surface tends to be about 50% gust and 50% lull. Gusts are more prominent in unstable conditions, such as when the water surface is warmer than the air.

Gusts and puffs are interchangeable terms. For sailors, gusts are important at all wind speeds. Note that the National Weather Service only reports gusts when the peak wind speed reaches at least 18 mph and the variation in wind speed between the peaks and lulls is at least 10 mph.

Gust Size

In 10-12 knot winds, fully-developed gusts generally extend about 100-200 meters across the wind and a longer distance upwind and downwind. In 20 knot winds, gusts may be double that size.

Bethwaite doesn’t address smaller puffs or geographic puffs, such as those near shore as the wind passes over obstacles. We’ll cover these in a separate article.

Gust Frequency

Gust and lull cycles repeat at random intervals. Although random, Bethwaite’s data shows the average gust/lull repetition interval is about 60 seconds, regardless of wind speed. This correlates roughly with the 100-200 meter average size of a gust in 10 mph winds. A gust moving downwind at 10 mph would move about 260 meters down the lake in 60 seconds.

His data also shows that a gust can remain on the water, moving downwind, for as long as 2-4 minutes before it gets slowed to the gradient wind speed and direction.

Gust Wind Speed

You may get a boost of 30-40% additional wind speed in a gust. The percentage increase in wind speed tends be be greater in heavier winds. Sailors that deliberately sail in gusts have a distinct speed advantage over those that don’t.

Gust Shape and Direction

When a gust first hits the water, it fans out like a cat’s paw. If you’re approaching a fresh gust, you want to be on the lifted side of the paw when sailing upwind and the headed side when sailing downwind.

Gusts cause the random, short oscillations in direction we see on the race course. After the initial gust fans out, the gust moves in a single direction, which may or may not be the same direction as the average wind direction. If the gust lasts long enough, it pays to be on the lifted tack within the new wind in the gust.

Surges and Fades

Besides localized gusts, we also know there are larger areas on the course with more or less wind. We don’t have a common term for these areas. We just say, “There’s more wind over there,” and sail to them if practical.

Bethwaite named these areas surges and fades and began to study them while writing Higher Performance Sailing. He wanted to learn how high performance skiffs could take advantage of them downwind.

What do we know about surges?

Bethwaite took hundreds of photos at one-minute intervals from a cliff overlooking Sydney Harbor. He meticulously transferred the outlines of darker water onto drawings in a time-lapse sequence. He got useful data about surges, but never had time to study their cause. Here are his conclusions:

- Surges are present in all kinds of weather conditions.

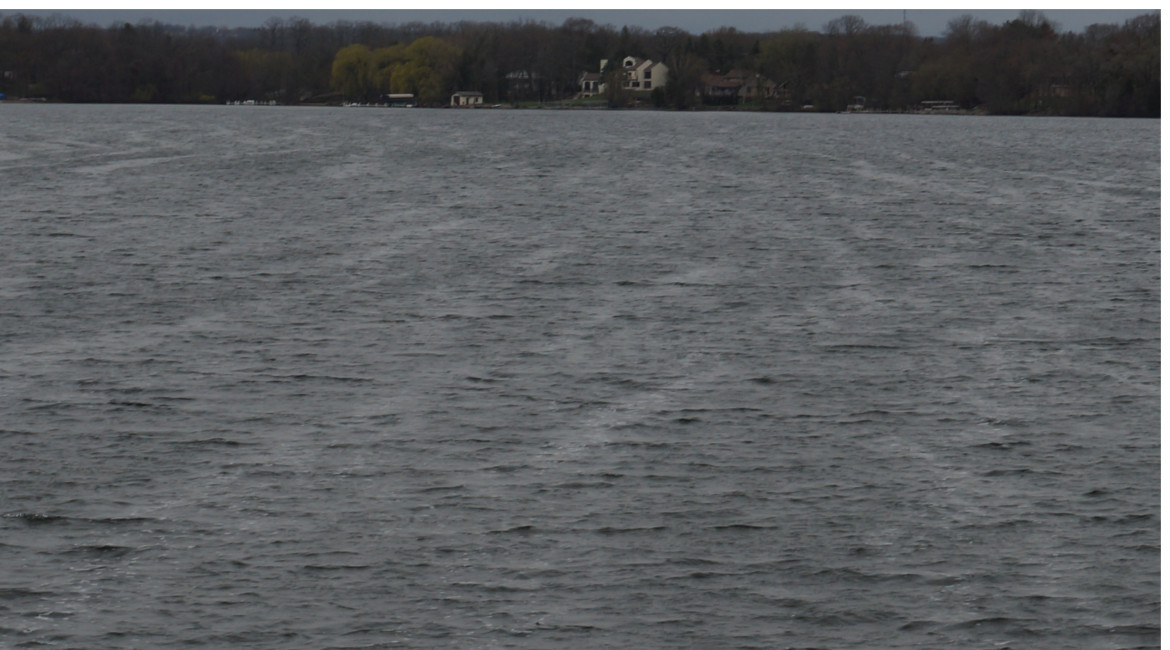

- Surges are mostly visible on the water, although sometimes just barely. The extra wind speed in a surge is perhaps 10-20% over the average, which is less than a typical gust.

- The Sydney Harbor surges were in the range of 1,000-5,000 meters in size. For smaller bodies of water, an estimate of 500-2,000 meters is more appropriate.

- Surges last for anywhere from 2 to 12 minutes.

- They usually drift downwind at about one-quarter of the wind speed. Sometimes they just appear and vanish. Occasionally a stationary surge appears and remains for awhile.

- Surges don’t behave consistently. They may disappear before you reach them.

Rolls

Rolls drive periodic changes in wind velocity and direction. They are different from gusts/lulls and surges/fades in two ways: 1) they are typically predictable and 2) they affect the wind direction and/or speed across the width of the course.

Rolls are rows of alternating updrafts and downdrafts caused by convection. The updrafts and downdrafts affect the wind speed and direction on the water. The changes occur at the edges of each row.

If there is adequate moisture and vertical temperature change, you will see the rolls as cloud “streets.” The clouds form in the updrafts. However, rolls are often present even if there are no clouds.

Characteristics of Rolls

Bethwaite and Stuart Walker provide the following data about rolls. Walker’s data is found in The Sailor’s Wind.

- Rolls are more likely to form when wind speed is greater than about 8 knots.

- Rolls cause regular oscillations in wind direction. The period is as short as 3 minutes in heavy air and as long as 10 minutes or more in light-medium air.

- The range of oscillations is anywhere from 5 degrees in light-medium air to 40 degrees in heavier air.

Using the Spectrum

Is all this data useful on the race course? It certainly isn’t a silver bullet, since there are so many variables to each element. However, using these categories as a framework may sharpen your approach to observing the wind. Here are ideas on what to look for.

Before the Race

Use the pre-race period to get a perspective on the relative importance of gusts, surges and rolls.

Gusts

We know gusts will be random, but their relative importance will vary. Are the gusts relatively strong? How large in size are they? How do they affect your heading? Practice seeing the course as areas of gusts and lulls.

Surges

If you believe Bethwaite’s data, surges will be present, although unpredictable. Because surges don’t cover the whole course and can last up to 12 minutes, they will give a distinct advantage to the boats that find them. Surges may the reason that one side of the course is usually favored.

You may be able to see them as larger areas of slightly darker water. As you sail upwind and downwind, you may notice periods when you’re sailing faster or hiking harder. As you near the start, you might be able to see a surge area and decide to head for it.

Rolls

Check the timing of oscillations. You may discover a pattern in the range of 3 to 10 minutes that you can use to predict the next shift after the start. For instance, if your observations show 3 minute shifts, and the last shift occurs two minutes before the start, you might decide to start nearer an end to get to that next shift first.

If you happen to see cloud streets, you may be able to predict the next shift, since it will occur as you sail under the edge of a row of clouds.

During the Race

Scan at two distances

Frank Bethwaite summarizes his son Mark’s approach to upwind and downwind strategy. Mark is a multiple Olympic champion in Lasers. Here’s a summary, quoted from Higher Performance Sailing:

When sailing upwind, scan at two distances:

-scan at the limit of vision (at least 200-500 m) to see whether the wind on one side of the course is stronger (surges) – and for backs and clocks (rolls). (Look at the water, flags, other boats, and any other indicators.)

-scan at closer range to track existing and forming gusts

When sailing downwind, scan for existing and forming gusts immediately behind the boat and a little to either side.

Connect the Dots

In general, try to connect the dots between the gusts, surges, and rolls. Stay in the gusts as much as possible while sailing to the surges and/or the next shift. the gusts.

If you see a fresh gust, also remember to position yourself on the lifted side of the gust.

Downwind

Bethwaite suggests that typical monohull dinghies should ignore surges for downwind sailing. That’s because a conventional boat doesn’t have the speed to access surges. The surges are likely so far away that they will be gone by the time the conventional boats sails to them. Only high performance boats can access these surges.

More About Wind

We like Bethwaite’s approach because it focuses on the observable changes on the wind. There’s lots more to learn about wind, including such things as the gradient wind, sea breeze, shore effects, and up-slope/down-slope winds. We hesitate to delve into these too deeply because they are full of mind-numbing terms. Perhaps we’ll take them up in future posts.

Related Content:

Upwind Strategy: Connecting the Dots

Seeing Wind on the Water – Improve Your Skills

Sailors Helping Sailors

Will you share your knowledge with your related Comments below?