Ever wonder why you sometimes can sail fast when the breeze feels light and there are no ripples on the water? Or why you might sail faster and point higher on one tack than the other? The answer may be wind shear and gradient. SailZing ran across a concise, readable summary of this topic by Shevy Gunter, who developed the drLaser website. The site is now dormant, but some archives exist.

We’re talking about differences in wind speed and direction between deck height and the top of the mast. If they exist, you could see as much as a doubling of speed (called a wind gradient) and/or a 30-degree change in direction (called a wind shear) at the top of the mast.

Key Points

Read Gunter’s article to understand the following key points:

- Wind shear and gradient can be present when air is vertically stable (no mixing between different heights).

- Factors influencing stability include vertical temperature differences, weather system, wind speed, and surface roughness. Warm air over a cold surface is a stable condition.

- Symptoms of gradient and shear include sail telltales responding differently up and down the sail, boat speed differences on different tacks, different helm feeling on different tacks. See a video example of this in the North Sails Let’s Talk Thistles Webinar.

- To account for gradient or shear, increase or decrease twist in the sails.

- Sometimes, as in a filling sea breeze, the direction of the air aloft will indicate the direction of the new wind. If so, sail toward the new wind as indicated by the wind aloft.

Additional Resources

We found more insights on wind shear and gradient in the following sources.

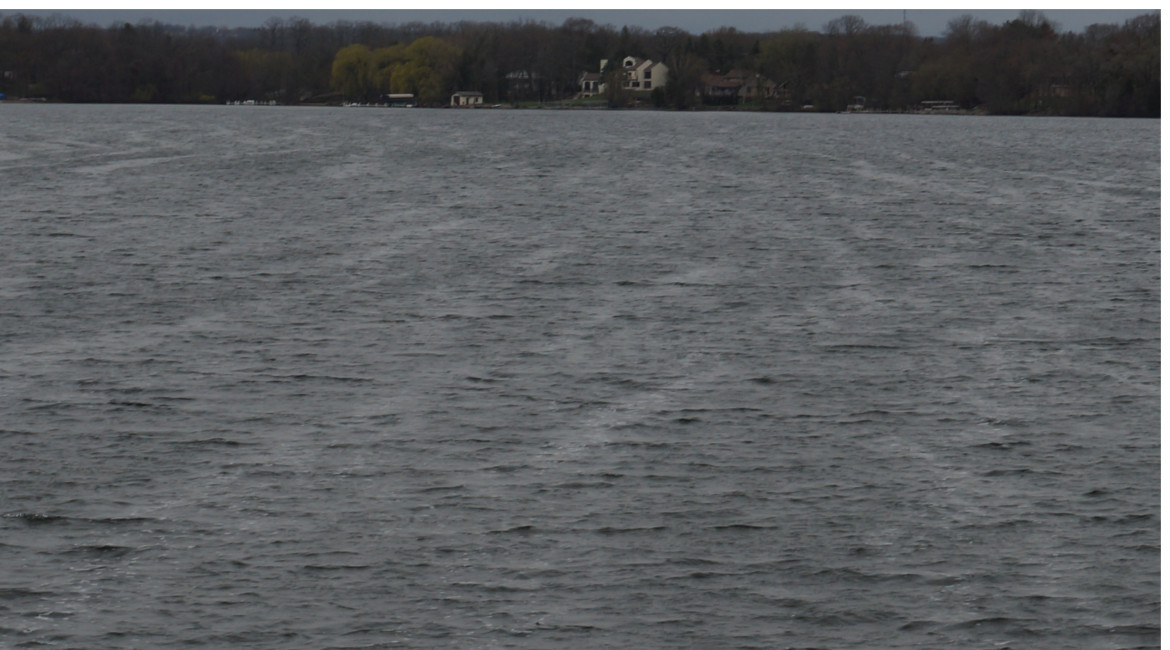

Lack of Surface Ripples May Indicate Gradient

In Higher Performance Sailing, sections 3.6 – 3.8, Frank Bethwaite describes his studies on wind gradients. Bethwaite measured wind speeds at deck height and top of mast in various conditions. In stable conditions (no mixing of wind at mat height with wind at surface), he found significant gradients even in 10 knot breezes. In unstable conditions, the gradient disappeared in breezes as low as 3-5 knots.

His key insight is that lack of surface ripples is a potential symptom of gradient. His data shows this to be true. The reasoning goes as follows:

- Air turbulence causes vertical mixing and thus reduces gradient.

- Turbulence near the surface also causes ripples on the water.

- Thus, surface ripples mean that mixing is occurring and the gradient may be small.

- Conversely, lack of surface ripples indicate a stable surface layer, which may mean that a gradient exists. (It also may mean that no wind exists!)

Luff Telltales, Sea/Lake Breeze, Strategy

In Championship Tactics, Gary Jobson and Tom Whidden reinforce several of Gunter’s points.

- Use the luff telltales on your sail to identify shear and gradient. If your sail telltales show proper trim at one height, but not at another, it may be due to shear. Regulate twist accordingly.

- A filling sea or lake breeze on a warm day in early spring is a classic shear and gradient situation due to the cold surface water with warm air above.

- If you discover a large shear, the wind direction at the top of the mast may indicate the direction of a persistent shift. Sail toward the new direction. In the northern hemisphere, the wind aloft is sheared to the right about 90% of the time.

Related Content:

Mainsail Telltales: A Better Approach

Light Air Boat Speed: Focus on Flow

Sailors Helping Sailors

Will you share your knowledge with your related Comments below?