Welcome to our series on upwind mainsail trim. This article covers Angle of Attack, which is Part 1 of a four-part unit on shaping your sails.

In this series, we’re presenting a comprehensive review of basic and advanced mainsail trim concepts. We want the series to be useful and understandable for all levels of sailors.

Our strategy is to start with small bites and build them into a complete picture of sail trim. We’ll use a visual approach, and give you questions to think about during the presentations. We’ll stay practical, using theory only as needed.

Each topic will have a video and outline version.

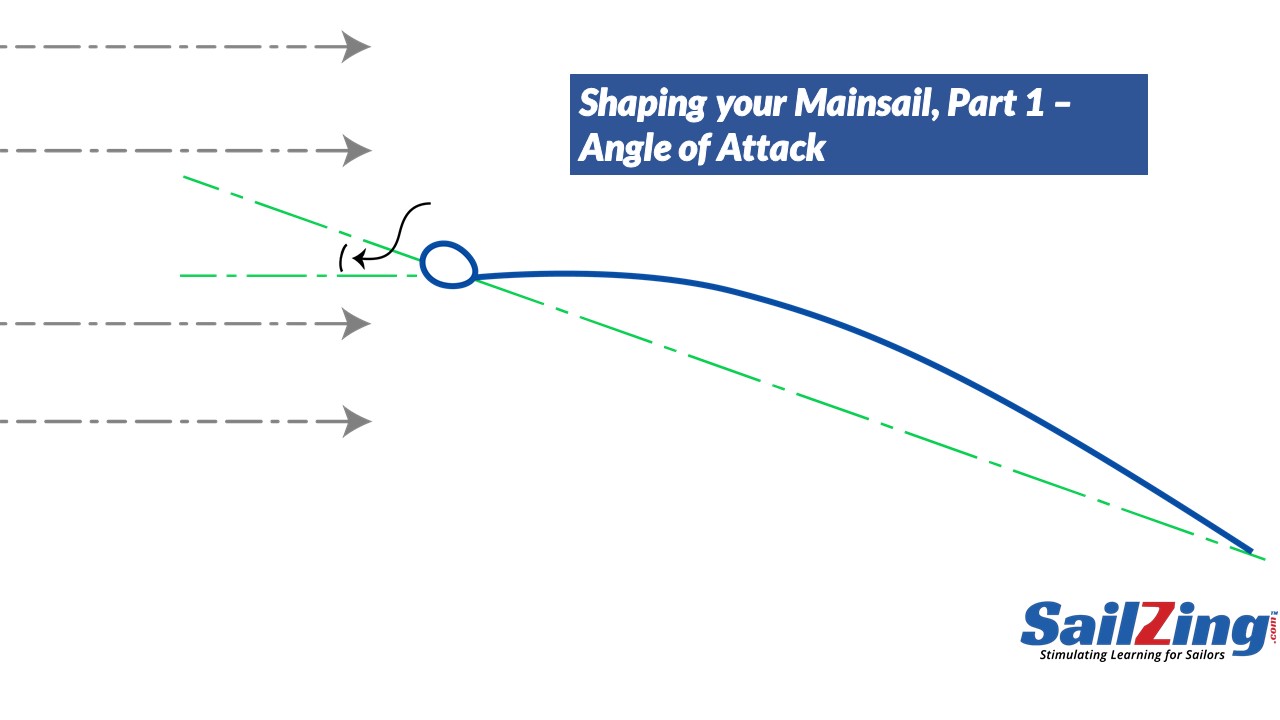

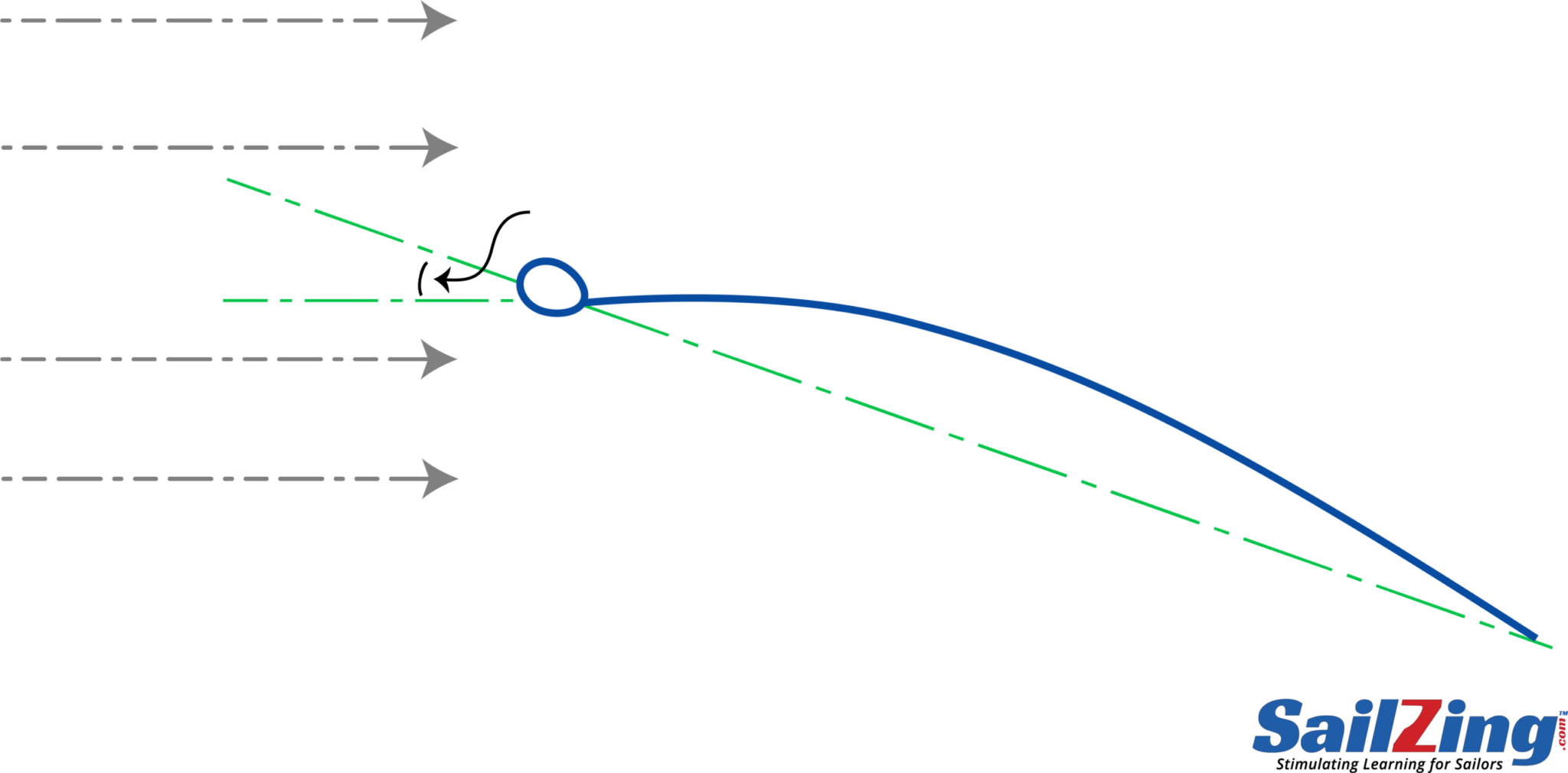

Angle of Attack Definition

Angle of Attack is the angle between the apparent wind and the chord line of the sail.

Why is Angle of Attack Important?

Sailing in the groove (best angle of attack) is the most important factor in upwind performance.

Sailing in the groove ensures that the sail deflects the wind while maintaining attached air flow on both sides. This maximizes lift and minimizes drag.

Most sailors have mastered the basics of sailing in the groove, but many have not mastered the fine points, such as:

- Sailing high. low, or mid-groove

- Reacting to puffs, lulls, shifts

- Finding the groove in light air

Controlling Angle of Attack

Controlling angle of attack is simple. You either adjust the boat’s heading or adjust the angle of the boom to the wind. To increase your angle of attack by steering, you simply bear off away from the wind. To increase angle of attack with the boom, you either pull in the mainsheet, or pull the traveler to windward.

Note that pulling in the mainsheet affects other aspects of sail shape, such as fullness and twist. If you want to adjust the angle of attack without affecting sail shape, you have to use the traveler.

Key Concepts – Lift and Drag

In our post, Lift and Drag, we covered the key concepts. These concepts lead to three simple optimal sailing points for upwind sailing.

- Most lift when attached flow on both sides (low groove)

- Best lift to drag ratio (most efficient) when windward side just begins to stall (middle of groove)

- Temporary higher pointing but less power with windward side stalling more frequently (high groove)

Groove Indicators and Cues

Controlling your angle of attack would be relatively easy if that’s all you had to worry about. Since you have many other things to focus on, it helps to have a variety of indications and cues to tell you when you’re not in the groove. In these next slides, we’ll point out nine different indicators and show how each is useful for different situations.

| Indicator | Cues | Comments |

| Feel of the boat | Pressure on legs. Boat feels free and lively. Slight tug on helm. Does feel improve with slight heading changes? | Best for medium/heavy air when you can feel changes. |

| Sound | Flapping sound from sail luffing. | Good wake up call. |

| Ripples in the water | Ripple movement will be ~45° to your heading | Good to anticipate shifts. |

| Sail | “Softness” along mast | Good for quick check that you’re not pinching. Softness (the beginning of a luff) means you are high in the groove. |

| Mast | Mast loading – curved to leeward at the spreaders | Unloaded mast means you are high in the groove. Mast will unload before sail luffs. |

| Shroud telltales | Angle relative to sail and rig | Good for spotting changes in apparent wind direction. One telltale should be slightly above skipper’s line of sight. |

| Forestay telltale (boats without a jib) | Angle relative to sail and rig | Good for getting ballpark heading in light air. Forestay telltale points just outside of leeward shroud in an MC Scow. |

| Wind vane | Angle relative to sail and rig | Good for detecting wind shear and setting twist (more later). Good for detecting if you are in the wind shadow of other boats. Unfortunately, this also helps other boats gas you! |

| Windward luff telltales | Streaming, lifting, reversing | Low groove: Streaming telltales indicate attached flow – max power. Mid-groove: Lifting 45° or vertically indicates slight stalling – most efficient. High groove: Lifting away from sail or reversing indicates more stalling – reduced power |

| Leeward luff telltales | Lifting | Good for indicating when you are below the groove – leeward telltales stall. Especially good in light air when other indicators are less reliable. Use a light-weight set of telltales and bear off until you are just above the stall point. |

Interactions and Changes

If you could watch the airflow over a sail in slow motion while sailing, you would see lots of variations in angle of attack. The best we can do is be aware of the interactions and changes that we can sense and control. Here are few of them. We’ll cover more about these in future posts.

| Change | Effect on Mainsail Angle of Attack |

| Adding a Jib | The presence of a jib decreases the mainsail’s angle of attack. This requires the main to be sheeted harder. |

| Puff or lull | A puff changes the apparent wind to increase angle of attack. Leeward telltale will likely stall. Easing the sail or dropping the traveler is the most effective way to compensate. A lull decreases the angle of attack. May need to bear off if lull persists. |

| Twist in mainsail | With twist, the angle of attack will be smaller further up the sail. In a uniform breeze, the upper sail will luff sooner. Reduce twist to increase pointing. |

| Pitching fore and aft in waves | Apparent wind in the top of the sail will change as mast pitches either forward or aft. This will affect angle of attack. Add twist to the sail to compensate. |

Mainsail Telltales – A Better Approach

Sailing Lulls Tips – Part II

Flat Water Steering

Shaping your Sail, Part 2 – Camber

Shaping Your Mainsail, Part 3 – Draft Shape and Position

Shaping Your Mainsail, Part 4 – Controlling Twist