Welcome to our series on upwind mainsail trim. This article covers Controlling Twist, which is Part 4 of a four-part unit on shaping your sails.

In this series, we’re presenting a comprehensive review of basic and advanced mainsail trim concepts. We want the series to be useful and understandable for all levels of sailors.

Our strategy is to start with small bites and build them into a complete picture of sail trim. We’ll use a visual approach, and give you questions to think about during the presentations. We’ll stay practical, using theory only as needed.

Each topic will have a video and outline version.

Special thanks to Will Hendershot, who contributed much wisdom to this article. Other sources include A Manual of Sail Trim, by Stuart Walker, Illustrated Sail and Rig Tuning, by Ivar Dedham, and North U’s Performance Racing Trim, by Bill Gladstone

Twist Definition

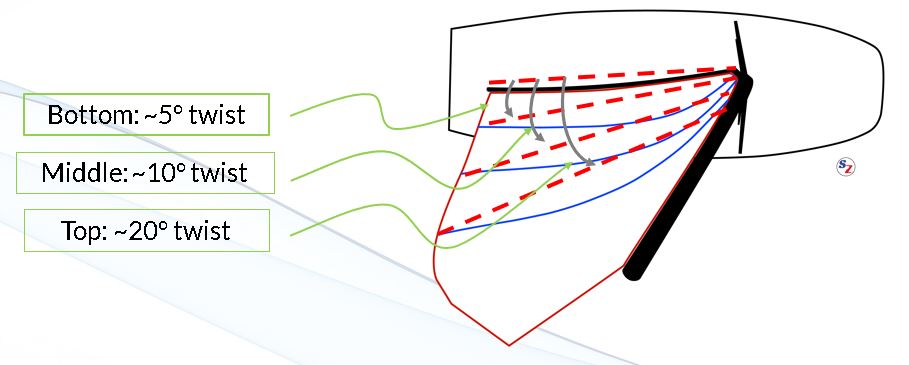

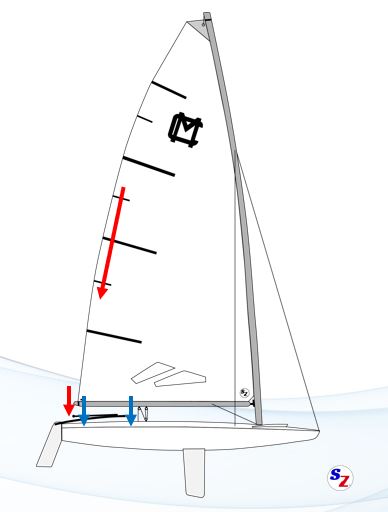

Twist is the angle of the sail’s chord lines compared to the boom. In the drawing, the sail has 5 degrees of twist in the bottom, 10 degrees of twist in the middle, and 20 degrees of twist at the top.

Sails have twist because the leech of the sail isn’t held in place by a boom or mast. Therefore, the leech will want to fall away when the wind hits it. This is why we often say that twist control is the same thing as leech control.

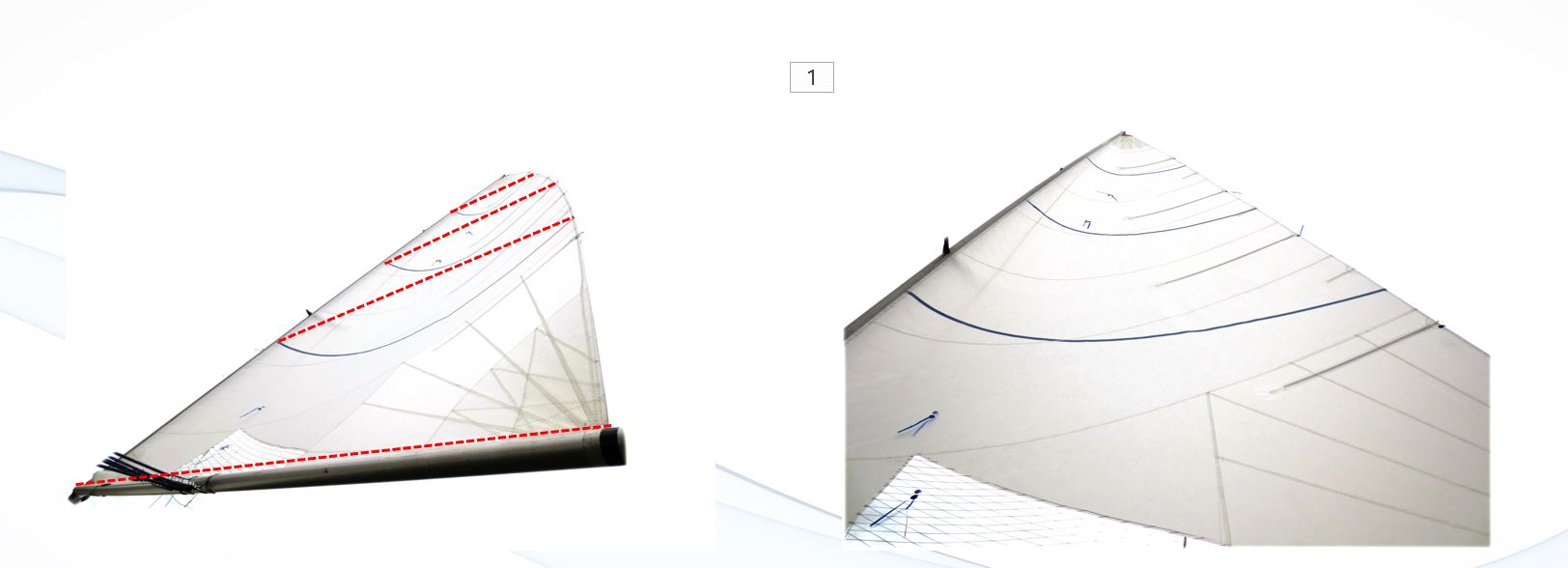

Example: Minimal Twist

Here, we’re showing a sail with almost no twist from the bottom view. We added the dotted chord lines to show this. Here’s a skipper’s view of the same sail. Can you see that that the sail has minimal twist from this view? One way is to notice how straight the leech is when viewed from the side.

Example: Uneven Twist

Here’s an unusual case of twist. The middle of the leech (arrow) is twisted slightly more than the top or bottom. You can tell by the abrupt change in curvature of the leech. I have heard this shape call mid-leech dump. There’s really no good reason for a sail shape like this.

Importance of Controlling Twist

Twist determines the performance of the upper one-third of the sail. The upper leech of the sail gets pushed around easily by the wind. So, if you want your sail to perform well, you have to control it.

Twist affects two aspects of the upper sails performance: angle of attack and camber.

- Changes the angle of attack

- Affects camber, since the controls for twist also affect camber

The performance of the upper sail is crucial:

- If the upper sail isn’t trimmed right, you’re losing out on a lot of power. Many average sailors don’t trim hard enough to power up the upper sail.

- When it’s time to depower, you should start by depowering the upper sail, since it contributes most to the heeling force.

- There are times, in very light air, when the wind speed and direction is markedly different at the top of the sail. Twist allows you to trim the sail differently at the top to take advantage of this.

When You Need Twist

Over-powered or footing

In both these cases you may need to twist off the top of the sail to depower it and reduce heeling force.

Wind stronger at top of mast

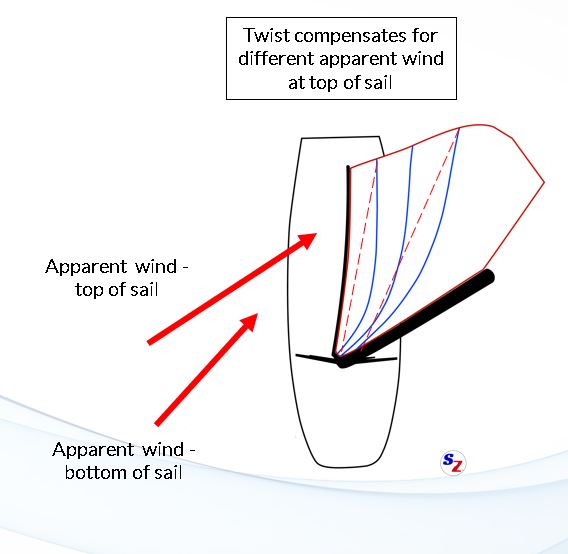

This usually occurs when there are no ripples on the water. For more on why this occurs, see our post on Wind Shear and Gradient. If the wind is stronger at the top, the wind at the top will be shifted for two reasons;

- First the apparent wind will be shifted due to the velocity change, just like it shifts in a puff.

- Also, the true wind will be shifted to the right, because the wind veers as it speeds up. This is due to the earth’s rotation, and is the same reason that water curves as it accelerates while entering a drain.

These direction changes require you to twist the sail to compensate. Additionally, because the true wind always shifts right (veers) with height, you may need different twist on each tack!

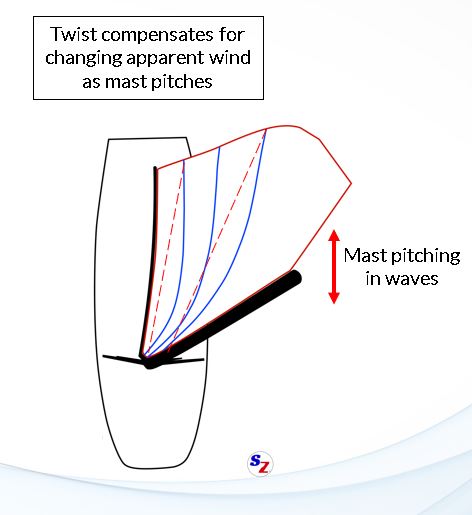

Boat pitching in waves

If the boat is pitching, the mast is swinging forward and moving faster when the boat is pitching down the back of a wave. Conversely, the mast is swinging back and moving slower when the boat is climbing up a wave. This changes the apparent wind and thus the angle of attack. This effect is largest at the top of the mast, somewhat smaller halfway up the mast, and least near the bottom.

You want twist in this condition, so that at least some part of the sail is trimmed properly no matter which way the boat is pitching.

Three Indications of Proper Twist

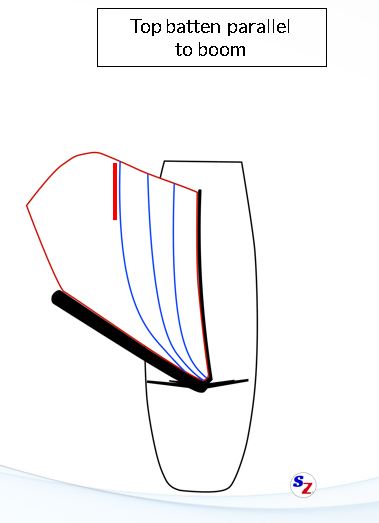

Top batten

If you’re not overpowered and no other unusual conditions exist, you will want the top batten to be roughly parallel to the boom. This keeps the top of the sail powered up, while letting the air flow smoothly off the leech.

If you want to point higher temporarily, the batten can be hooked in slightly, perhaps parallel to the centerline of the boat instead of the boom.

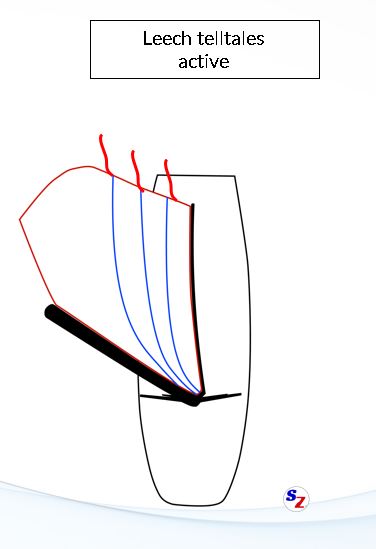

Leech telltales

In light to medium air, if your sail is trimmed right, the leech telltales will all be intermittently streaming and disappearing behind the sail, especially the telltale on the upper leech. It helps to have telltales on the end of all the battens in the sail to see if the leech is properly trimmed at the top, middle and bottom.

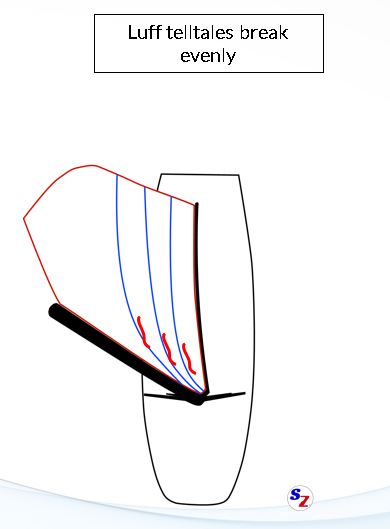

Luff telltales (jib or main)

Another tip is to try to get all the windward side luff telltales behaving the same way. Sailmakers put telltales on jibs at three levels for just this reason. The jib trimmer adjusts the jib leads and sheet tension to get all the windward telltales to start breaking at the same time. You can do the same with your mainsail. If you have too much twist, the telltales near the top will be stalling, while the bottom tales will be streaming.

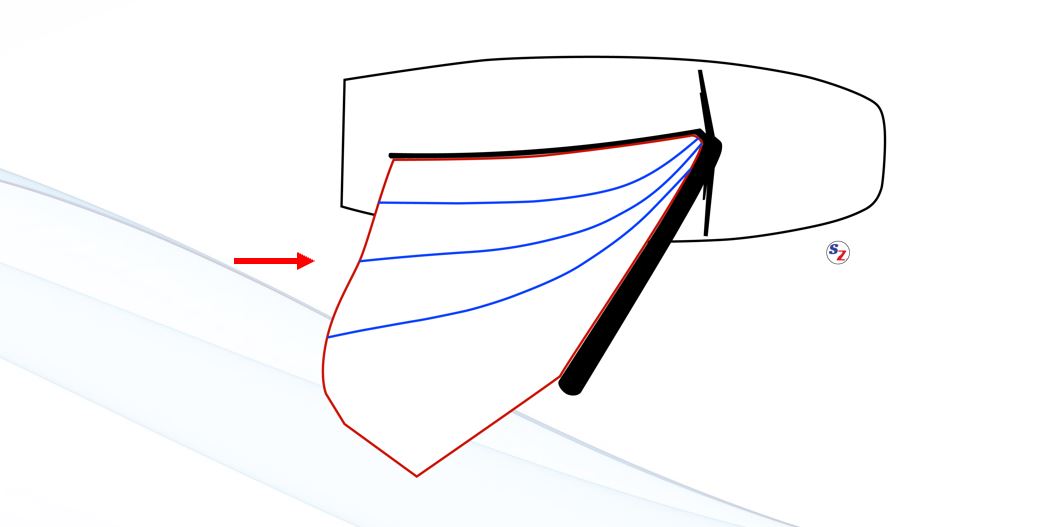

Controlling Twist – It’s All About the Leech

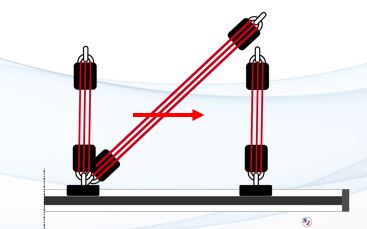

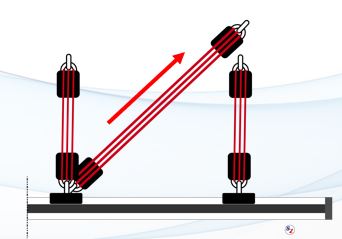

The mainsheet and the vang are the two primary controls, and they both work by pulling the end of the boom down to tension the leech. There are some differences between the vang and the mainsheet, so let’s look at them more closely.

Mainsheet

The mainsheet pulls the boom down from either the end or middle of the boom. If you have a rear traveler or a boom bridle, the main is pulling directly down on the end of the boom. If you have a center traveler, it’s pulling down on the center of the boom.

Vang

The vang pulls down from the front of the boom. If the boom can flex, the end will be able to rise, even with the vang tight.

This leads us to the concept of vang sheeting. In vang sheeting, you tension the vang to flatten the sail and then you ease the mainsheet in the puffs. Easing the main allows the boom to move out to reduce the angle of attack down low and rise to let the leech to twist off to depower the top of the sail. Vang sheeting is very important, but it has limitations, which we’ll discuss shortly.

Cunningham

By pulling the sail’s draft forward, the cunningham can flatten the upper leech, adding twist. This has more effect in sails with large roach (e.g., C scow).

Traveler Position

Where you position the traveler can also affect twist. If you drop the traveler to leeward to depower, the mainsheet is still pulling directly down on the boom, so the twist does not change much.

On the other hand, if you leave the traveler on center and ease the main to respond to a puff, the boom will move out and rise, since the main is no longer pulling directly down. This again relates to vang sheeting.

Interactions and Challenges

Heavy Air, Crew Weight, and Twist

Heavy air is a challenge, especially for lighter crews. The problem in heavy air is drag, especially if you depower by luffing too much. It’s best to keep as much of the main loaded and depower the top of the sail with twist. This reduces heeling force.

Heavier crews have an advantage because they can put more load on the sail. When the sail is loaded, the leech will twist off, since it is not supported by the mast or boom. So, heavier crews get the benefit of being able to twist off the leech more than lighter crews.

Lighter crews must find ways to de-power that still minimize luffing. One choice is to use a flatter sail, especially one with less depth up top. This sail will have an open leech and will twist off more easily in puffs. Of course, lighter crews also need to use the depowering controls sooner than heavier crews.

De-powering with vang vs. traveler

Another challenge is the sequence of using your controls to de-power. The vang is an important control for de-powering, but so is the traveler. What combination should you use?

Vang

As we’ve seen, vang sheeting is effective, because the vang flattens the sail but also allows the end of the boom to rise when the mainsheet is eased. This sounds ideal, but has limitations.

- If the vang is too tight, easing the main may not be enough to twist off the top. You may have ease very far to depower, which makes responding to puffs difficult.

- A too-tight vang may distort the sail shape. You may see large overbend wrinkles or even invert the draft of the front of the sail.

- Without enough twist, the boat will be hard to steer due to weather helm and will be very unforgiving. If you steer down too much, the tight vang will expose a lot of sail to the wind and knock you over. If the boom hits the water it won’t be able to rise and will drag the boat over. Many capsizes are caused by too much vang.

Traveler

Dropping the traveler to depower gives you more forward driving force, reduces heeling force, and reduces weather helm. This makes the boat more forgiving. The extra forward force gives you speed that makes up for the lower heading angle. Some cautions apply:

- If you drop the traveler you’re depowering the whole sail, and you need to sheet harder to reduce twist and keep the top of the sail more powered up.

- You also need to pull it back up as the breeze lightens.

The best combination of vang and traveler depends on the conditions. Experiment and learn different combinations, based on the feel of the helm, the size of the waves, the sharpness of the gusts, and the ease of adjustment of the vang and traveler. All this will also depend on your boat’s rig and sail design.

Inducing twist in light air

Getting twist in light air can be a challenge, since the wind may not be strong enough to open the leech. Here are things you can do to induce twist in light air.

- Minimize the downward tension on the boom. This means light tension on the mainsheet, no tension on the vang, and the traveler on center or even to windward a bit. Pulling the traveler to windward is a trick that some boats use to further reduce downward tension on the boom.

- Heel the boat. This lets gravity help open the leech and reduces the wetted surface. Many sailors don’t heel aggressively enough in light air. However, be careful not to overheel the boat, since too much heel reduces sail power and driving force.

Shaping your Sail, Part 1 – Angle of Attack

Shaping your Sail, Part 2 – Camber

Shaping Your Mainsail, Part 3 – Draft Shape and Position

Wind Shear and Gradient Effects on Trim & Strategy

MC Scow Sail Trim – Sailmaker Discussion