SailZing Contributor

In the MC class, your biggest opportunity to pass boats occurs while beating to windward. It separates the top 10 percent of the fleet from the rest. If you want to be a better MC-Scow sailor, boat speed is the first place to start. In this series of articles, MC-Scow sailor and SailZing contributor Henry Chesnutt shares his secrets to speed that got him to the top of the fleet in a few short years.

Introduction

Helming a boat upwind is the most important skill to develop for racing MC Scows. The goal is to find that magic combination of pointing angle, heel angle, and sail shape where the boat awakens, and to then maintain that equilibrium in the face of changing wind speeds, direction, and wave conditions for the entire race. The difference between being in the groove and being slow can be as simple as pointing a few degrees lower, putting a little more weight on the rail, or letting the mainsheet out two inches. It is a subtle affair. The groove can only be achieved when the boat becomes an extension of the skipper. Muscling the boat to windward with clenched teeth and white knuckles is a sure way to find transoms quickly; a light touch and responsiveness to the boat’s needs should be cultivated. In the words of American writer and sailor John Rousmaniere:

The goal is not to sail the boat, but rather to help the boat sail itself.

Foundation 1: Heel

Heel Angle: the angle of the boat against the water

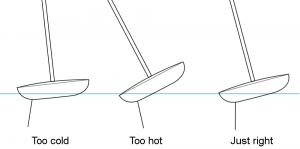

Every top scow sailor knows that heel angle is the single most important aspect of speed. In his book Sailing Smart, Buddy Melges states “This [heel] angle varies quite widely class to class or from one design to another, but it always applies, no matter how strong or weak the wind.” Heel angle is important for a number of reasons, but primarily because it controls the angle of the board in the water. When the angle is too high or too low, the board does not dig as deeply as it could, resulting in less efficient hydrodynamic lift and more side-slippage.

You want the board to reach as far down as it can, maximizing the sideways surface area and lateral force that it is designed to generate. Any time the board deviates from this maximum down angle, the lateral resistance offered by the board decreases, thus making the boat slip sideways, downwind.

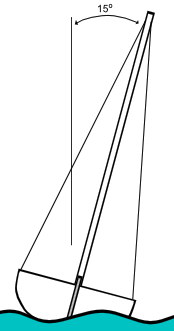

On Lasers and other centerboard dinghies, the board exits the boat straight down. Such boats must therefore be sailed flat to keep the board as deep and efficient as possible. Scows are unique because their bilgeboards (or leeboards) exit the hull from the sides, so the boat must be heeled up in order to maintain a vertical board. The appropriate amount of heel on a scow is when the mast is 10 to 15 degrees off vertical, where the water is about one inch below the leeward rail. If water comes above the rail in flat water you’ve gone too far.

Related Content:

Andy Burdick on Angle of Heel – see video at 2m20s

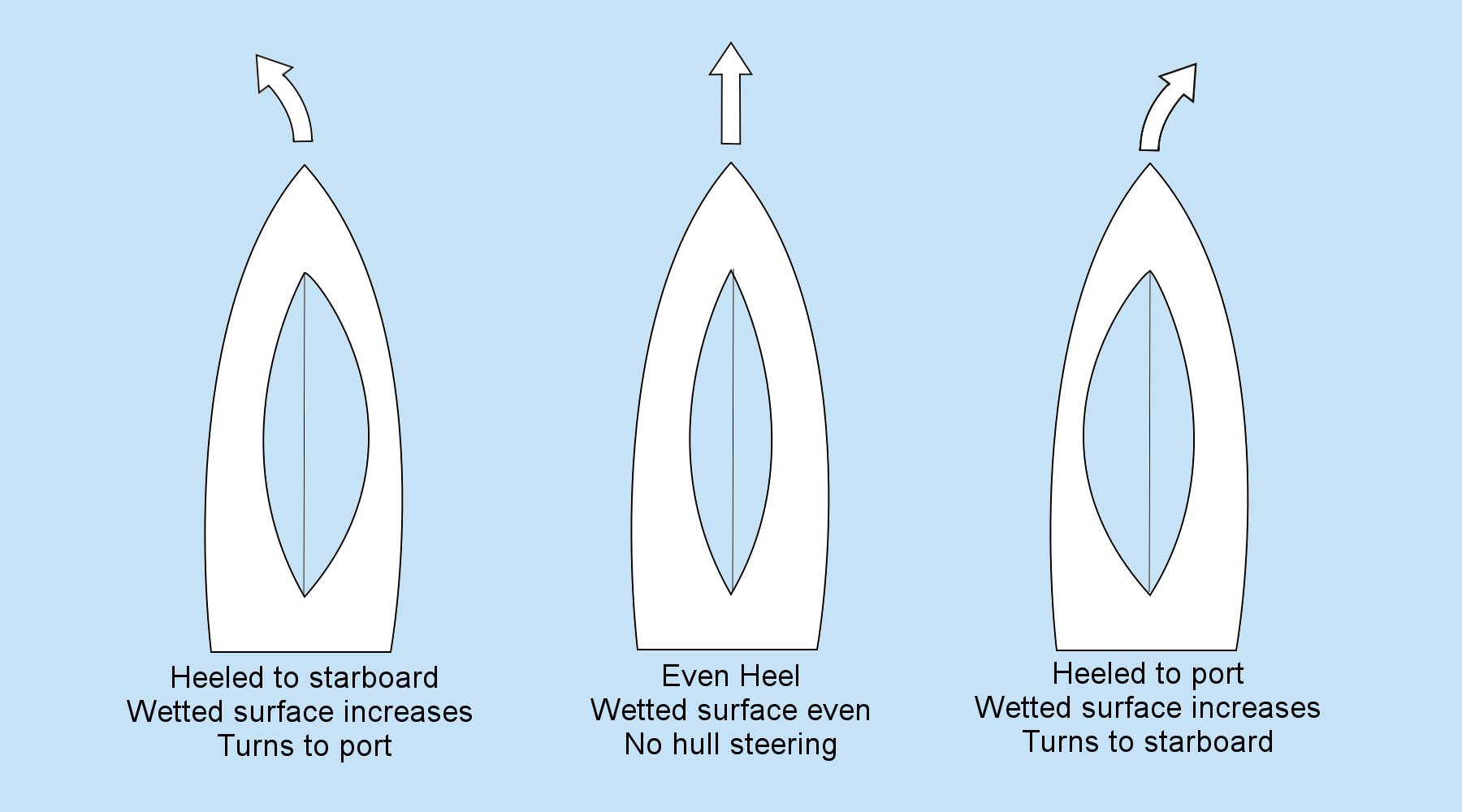

Heel is also critical due to an effect called hull steering, which is the tendency for the boat to turn opposite the direction it’s heeling.

Hull Steering: The tendency of the boat to turn opposite the direction it’s heeling.

For those of you who have sailed a centerboard dinghy, this effect is obvious, and is critical to handle the boat correctly. By heeling the boat, you can turn, minimizing or eliminating the rudder movements that usually accompany such a maneuver. Due to the unorthodox hull shape of the MC, it’s not easy to spot this effect if you aren’t looking for it, but I’m convinced it’s an effective method of minimizing rudder drag and increasing speed. Heel more and the boat will want to turn into the wind, heel less and windward helm decreases.

This occurs because the wetted-surface of the hull against the water changes as the boat heels, resulting in one side of the hull having more buoyancy than the other. As the boat moves forward this added buoyancy tries to equalize, turning the boat.

It should be mentioned that another reason heel angle matters is that it decreases drag by minimizing the wetted surface of the hull in the water. When the boat is flat, its wide hull offers inordinate surface area, heeling up the boat decreases this surface area significantly. I have heard that this alone can be responsible for a 10% difference in speed. This effect matters more when the wind is light, and is of more interest downwind.

Foundation 2: Rudder

To sail fast you need to think of the rudder not as a steering wheel but as a brake. Any pressure exerted on the rudder is energy exerted against the boat’s momentum. Every time you fight windward helm (the boat’s tendency to round up into the wind) you are holding the boat back. The more you fight it, the slower you will go relative to the helmsman one boat to windward doing it correctly. Nearly everything we do for the rest of the tutorial comes back to maintaining heel while minimizing rudder movements. Any use of the rudder can be minimized by utilizing the hull steering properties illustrated in Foundation 1. We’ll go into more depth on this later.

Windward Helm: the boat’s tendency to round up into the wind

Your rudder movements should be slow, and should rarely leave the inside of the cockpit. You can be more aggressive on the tiller in heavier wind, while in light wind even the slightest tug can have a hemorrhaging effect on the boat’s momentum.

Foundation 3: Mainsheet

The mainsheet is by far the most important sail control. It is the primary mechanism for controlling the angle of the sail relative to the wind (see angle of attack on airplanes), and determines whether the sail establishes laminar flow or stalls (no power) from being over-trimmed. For any apparent-wind direction there is an ideal trim for the mainsail, and it’s your job to find it all of the time. The best way to automate this is to buy yourself some SailZing StayTales Telltales… or just some cassette tape, VCR tape, or yarn. Slide on, tie, or tape them to your sidestays at head height, where you can see them easily in your peripheral vision. I like at least one more higher up in case my crew’s head is in the way. These telltales are your guide to trim the sail. Do not ever sail without them.

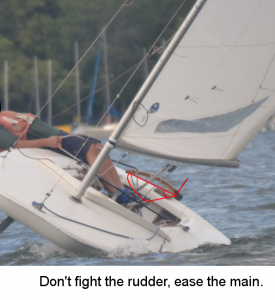

The mainsheet’s second mechanism is to de-power the boat when it is overpowered. A boat is overpowered when you (and your crew) are fully hiked out, the mainsail is pulled in, and you cannot maintain the proper heel angle. When this occurs you must immediately dump some wind out of the sail to maintain heel, then as soon as the boat starts falling back down the main can be slowly cranked back to it’s tight position. If you find you can’t pull in the main all the way without over-heeling, you need to add more weight or, more likely, de-power. In another article, we will talk about how to de-power the mainsail using other methods besides the mainsheet. For now you need to ingrain in your head that it’s better to let the mainsheet out and maintain heel than it is to over-heel. Don’t listen to any drivel about “You gotta keep the sail full” that you might hear. The sailor in the photo has just to ease the sail a few inches to avoid pulling so hard on the rudder.

You really can’t play the mainsheet too much. Mainsail trim needs to be re-assessed ever few seconds. Andy Burdick, winner of more scow championships than anyone can remember, prefers to remove the mainsheet cleat from his boats.

Related Content:

Foundation 4: Hiking and Body Placement

Your body is the only piece of mass on the boat that can freely move about. An MC weighs 420 pounds, so many skippers can make up a third (with crew half) of the total weight of the boat on the water. The boat feels and will respond to many movements that you make. The more effectively you can manage your weight the better, so proper hiking technique and ease of movement is required. If you have trouble moving around in the MC, try observing a better sailor with your body type move in their boat. Laser sailors have to hike out frequently, so check out the video below on hiking technique with Steve Cockerill. You will want to have your hiking straps adjusted so that your butt sits off the edge of the gunnel by a few inches, so you can comfortably lean out without fear of slipping out.

Related Content:

Steve Cockerill articles on SailZing

The fundamental idea here is that the harder you hike while maintaining proper heel angle, the faster you will go. Sailing upwind is similar to shooting a watermelon seed between your thumb and forefinger, and getting more weight out is the equivalent of squeezing the seed harder.

Your body placement is going to be the primary way you utilize hull steering effects to maneuver the boat. By moving your weight out it will take less exertion on the rudder to combat windward helm. By letting the boat heel up you increase windward helm and your ability to pinch higher on the wind, which is very useful when there is a boat directly to leeward that you risk falling into their ‘lee bow’ wind shadow.

Pinching: Also known as feathering up, refers to pointing higher into the wind than normal.

Putting it all Together

Now that you have an understanding of heel, rudder, mainsail trim, and bodyweight, you have the pleasure of discovering how they work in concert to work the boat upwind with least resistance.

Here’s my recipe:

- Use only the mainsheet and bodyweight to both maintain heel and minimize rudder movements.

- The more you work the mainsheet, the less you have to fight the rudder.

- The more you can use your weight to steer with the hull, the less you have to use the rudder.

- Combine this with maintaining that heel angle and you will go faster.

Say, for example, you’re steering upwind in medium wind, heel is good, mainsheet is pulled roughly 8 to 12 inches between the blocks. You’re sitting on the edge of the gunnel as close to the traveler track as possible, and you feel only a slight tug from the tiller. The boat encounters a puff. Immediately you dump the mainsheet as much needed to maintain the heel angle (this can be as much as a whole arms-length in gusty conditions, whatever is required). As you ease the mainsheet, you hike out and feel the rudder response. Don’t fight it; let the rudder head you up into the wind. As the boat approaches the new close-hauled angle (this angle gets closer to the wind in more pressure as the rig and board gets more efficient) you slowly trim the mainsheet tight again, and move more weight out to lower the heel and decelerate the turn.

The faster you can react to the puff the better. Good sailors look up the course to see wind that’s approaching them so they can be proactive about hiking out and/or de-powering when the puff hits.

Whenever the boat over-heels and you can’t hike out in time, your default instinct should be to dump the main by easing the mainsheet. This will spill wind from the sail and keep you from over-heeling. Remember the acronym EHT: Ease, Hike, Trim. Ease the sail, hike yourself out, then trim in while monitoring the tiller pressure. Don’t forget to pull the mainsheet back in as soon as the boat stops overheeling. You’re trying to keep that heel constant, and you achieve this with the mainsheet.

If this is all new to you, the next time you race try ignoring all the other boats and focusing all of your attention on getting this right. You may be surprised.

Getting There: Drills

Nothing from this scow sailing speed guide will click if you don’t practice. I recommend you take your boat out in a wind speed that you can comfortably sit on the side of the boat without being overpowered. You need to increase your awareness of what the boat is telling you in two primary areas: heel and tiller pressure. These need to become instinctual for you. Try the following exercises the next time you’re sailing solo:

- Sail up the lake for 10 minutes on a close-hauled course paying particular attention to the angle the sidestay makes with the horizon. Every 10 seconds or so you will verbally call out the heel of the boat. Your goal is to increase your awareness of the heel angle, so don’t worry if it’s all over the place. You can also try closing your eyes while you continue to call out heel angle. Eventually you’ll want to condition yourself to get physically uncomfortable when the heel angle is not perfect.

- Sail up the lake for 10 minutes on close-hauled while holding the tiller as lightly as possible, with just the tips of your fingers. Imagine you’re holding a small, fragile animal. Every 10 seconds verbally evaluate the pressure you feel on the rudder on a 1-5 scale. Your objective is to increase your awareness of what the rudder is telling you, minimizing that pressure will come later. You can also tie a line to the rudder and try steering upwind with just the line.

- Sail up the lake for 10 minutes on close-hauled while observing the angle the telltales make relative to the mainsail, and constantly trimming the mainsheet in and out. Your goal is to observe how powered up the sail feels as the telltales and mainsail move relative to each other. When it feels powered up, say aloud “Powered up”. When the sail feels stalled, say “Stalled”.

- Sail up the lake trying to maintain perfect heel angle, and a powered-up mainsail. Use only the mainsheet and your body weight. Every couple seconds, rate the speed of the boat on a scale of one to three where one is slow and three is top gear.

Sailors Helping Sailors

Will you share your knowledge with your related Comments below?