Struggling with boat speed? Want to sail more by feel? Understanding and managing helm balance will help. In this post we’ll discuss the factors affecting upwind helm balance and give examples of how to apply them. We’ll cover downwind helm balance in a separate post.

This article contains clarifications and corrections to the original version.

What is Helm Balance?

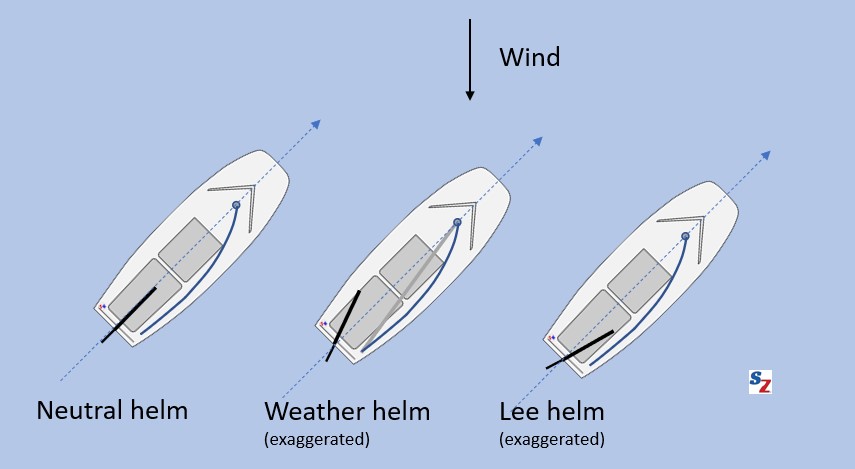

Helm balance refers to the pressure you feel on the tiller when sailing in a straight line. A helm is said to be either neutral, weather, or lee.

- With a neutral helm, there’s no pressure on the tiller. If you let go of the tiller, it stays centered and the boat continues in a straight line, assuming no waves or wind changes.

- Weather helm means there is pressure trying to turn the boat to windward (i.e., to “weather”). You feel this pressure in the tiller and must pull the tiller to windward against the pressure to keep the boat sailing straight.

- A lee helm has pressure trying to turn the boat downwind (i.e., to lee or leeward). You must push the tiller to leeward to keep the boat sailing straight.

What Causes Helm Pressure?

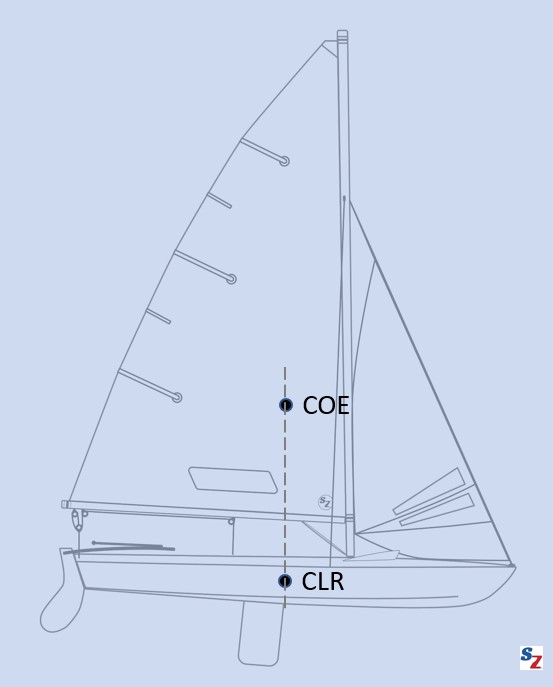

Pressure in the helm occurs when the force of the sails is too far forward or aft compared to the boat’s natural pivot point. Let’s break this down.

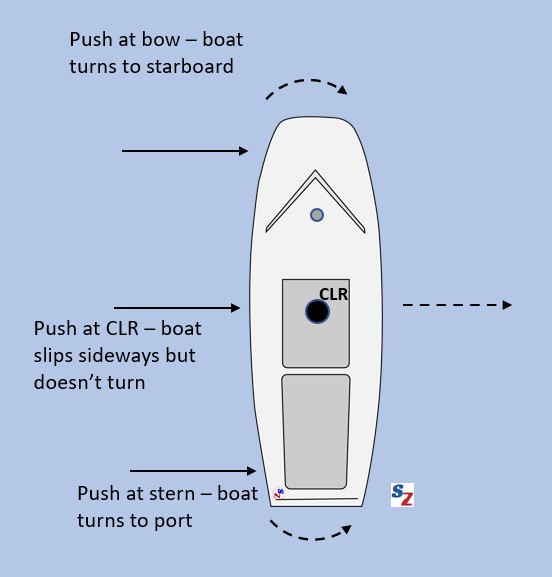

We all know that if you push sideways on the bow or stern of a boat at the dock, the boat will turn. If you find the right place to push – somewhere near the middle of the boat – the boat won’t turn, but will just slip sideways. This place is called the center of lateral resistance (CLR).

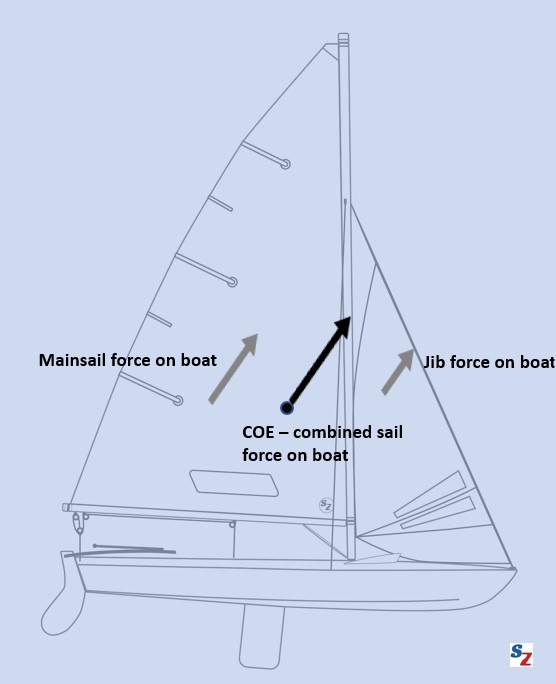

When sailing, the sails push sideways and forward on the boat at many different places – the mast, forestay, side stays, and the mainsheet and jib sheets connected to the blocks. The jib exerts its force toward the front of the boat and the mainsail’s force is further back. The combined force of all the sails is at a point somewhere near the middle of the boat. This point is called the center of effort (COE).

If the COE is closer to the stern than the CLR, the boat will want to turn upwind, resulting in weather helm – you must pull the tiller to windward to keep the boat sailing straight. With the COE forward of the CLR, the boat will try to turn downwind, resulting in lee helm. If the COE and CLR are aligned, the boat will sail in a straight line without any pressure on the tiller.

Moving the COE – Examples

To experience the effect of COE placement, sail a boat with the jib alone. The jib’s COE is far forward of the boat’s CLR and you will have lots of lee helm. Now furl the jib or let it luff and sail with the main alone. The COE is now behind the CLR and you will have weather helm.

Windsurfing gives us another example. Windsurf boards don’t have rudders. The sailor steers by pivoting the sail forward and aft, thus moving the COE. To go straight, the sailor moves the sail forward or aft until the COE matches the CLR. To turn upwind, the sailor moves the sail aft. And to turn downwind he/she moves it forward.

Why Does Helm Balance Matter?

“Whatever boat you sail, neutral helm is the default, but always explore a few variations one way or another.”

Mike Ingham in Striking a Balanced Helm – Sailing World.

“In general, about 3-5 degrees of rudder angle is fastest when sailing to windward.”

Dave Dellenbaugh in Steering, from Speed and Smarts.

Ingham favors a neutral helm – tiller on center. Dellenbaugh claims that a small amount of weather helm, such that the tiller is deflected 3-5 degrees to windward is faster. Let’s explore these statements by looking at three effects of helm balance: rudder drag, rudder lift, and skipper feel.

Rudder drag

A neutral helm is fast. With an unbalanced helm, you must pull or push the tiller away from center. The uncentered rudder causes drag and slows the boat down. To experience this, take the rudder off your boat and try to run or walk fast in shallow water while holding the rudder in the water. It’s much harder to run when the rudder is not centered.

You can also see and hear the drag from a rudder that’s not centered. The wake behind the rudder won’t be centered, and you will hear bubbles gurgling if the rudder stalls.

Rudder lift

Some experts believe that a slight amount of weather helm actually improves performance upwind, despite the increased drag. The water flowing over the uncentered rudder creates lift as well as the drag we just discussed. These experts claim that the lift actually pushes the boat to windward.

Other experts dispute this. Dave Ullman says that weather helm is not lift. He says that the best drivers can sail with a totally neutral helm. Less skilled drivers need a slight weather helm to feel the boat.

This dispute is interesting, since top sailors seem to disagree. We looked for a resolution and here’s what we found.

- C.A. Marcaj, in Sailing Theory and Practice, spends several pages discussing this (Part III, Section 3). He shows how the rudder contributes to lift, and states that experiments with racing dinghies show that most of them perform better to windward with a slight weather helm.

- In our post Common Pointing Problems, we refer to an older Buccaneer tuning guide with data showing that a small amount of weather helm is beneficial in wind up to about 13 knots. It’s hard to say whether this data is definitive.

- In our post Understanding Leeway, we refer to an article by Andy Horton claiming that optimum rudder angle (i.e., the number of degrees of weather helm) plus a boat’s leeway angle should equal 5-7 degrees. Boats with small leeway angles need more weather helm, and boats with large leeway angles need less weather helm. Andy shows how to measure leeway and rudder angle to optimize.

Based on the above, we conclude that weather helm does provide lift, but that some boats need little or no weather helm for optimum performance, while others need a slight weather helm, but no more than 3-5 degrees.

Skipper feel

Regardless of the lift/no lift dispute, many skippers like a small amount of weather helm when sailing upwind. If the amount of weather helm changes, they can feel this instantly and react. With a neutral helm, it’s harder to feel changes. We’ll talk much more about this in the sections below.

Managing Helm Balance

You have many ways to change the COE and the CLR of your boat. It helps to have options when you’re trying to achieve just the right helm balance. Here are six options.

#1. Heel angle

Angle of heel has a huge influence on helm balance, and is the tool every sailor should use to minimize weather helm. As a boat heels over, weather helm increases. This increase is dramatic in most boats. If you fight the weather helm by yanking on the tiller, the boat slows down. If you’re not aggressively controlling heel angle, you simply won’t be as fast.

Why does overheeling increase weather helm?

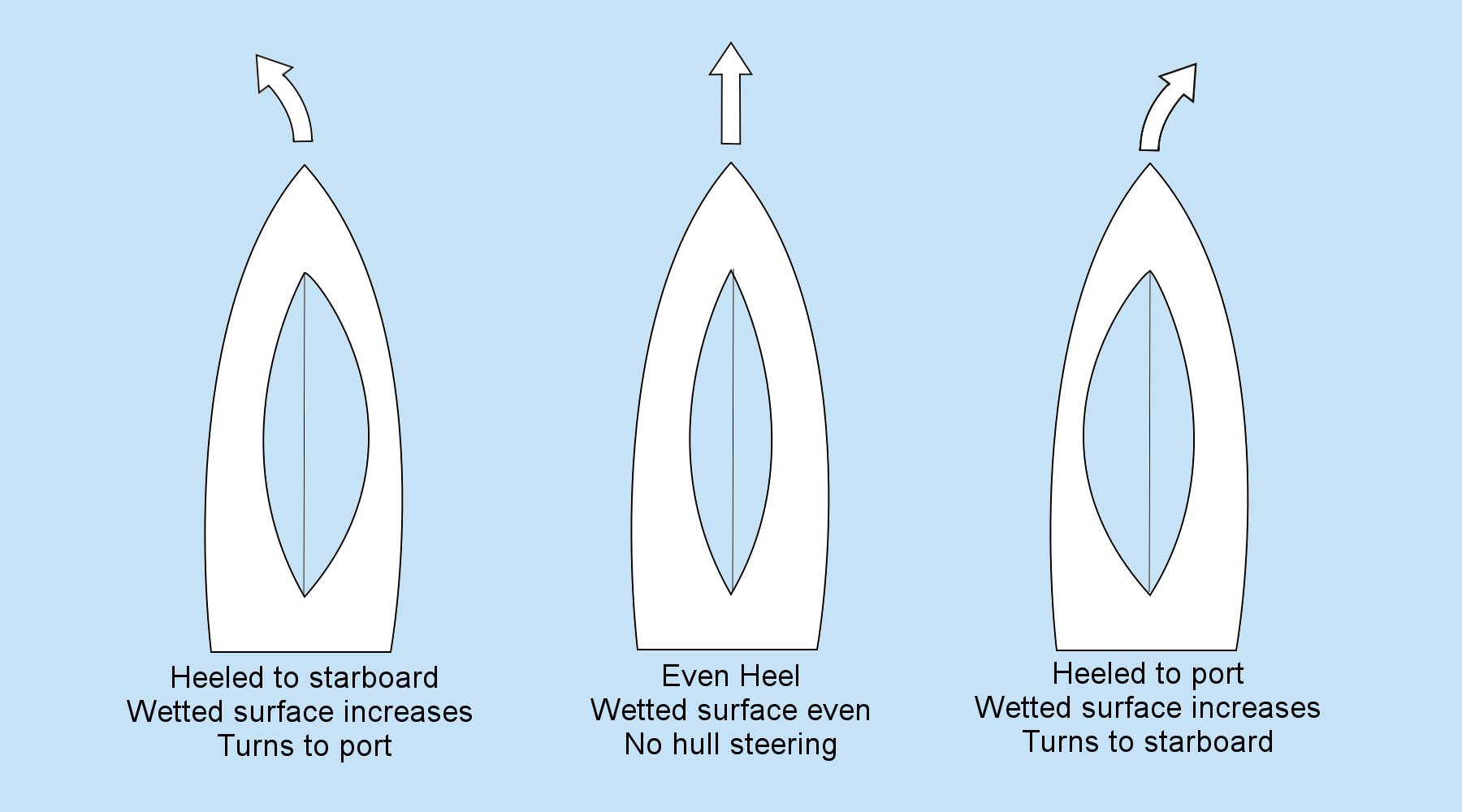

- The CLR effectively moves forward as the boat heels. This is because the shape and size of wetted surface of the hull in the water changes. This effect doesn’t depend on the sails – you can turn any moving boat by heeling it in the opposite direction you want to turn.

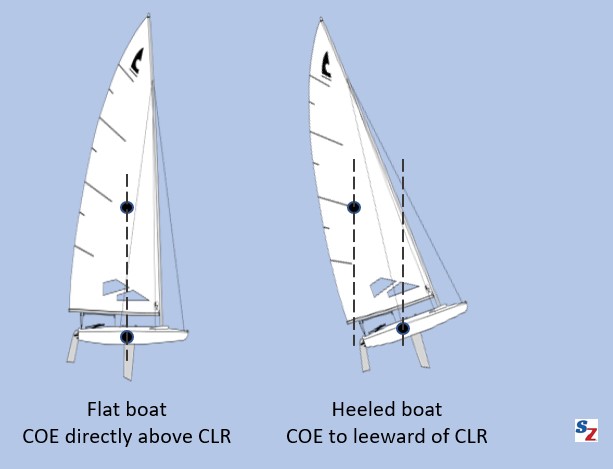

- In addition, when the boat heels the COE moves to leeward and becomes misaligned with the CLR, which also turns the boat to windward.

#2. Mast rake

Just like the windsurfer, you can change the COE by raking the mast further forward or aft. You can’t change the rake as much as windsurfer, but even an inch or two can make a difference in helm balance. Tuning guides suggest the proper amount of mast rake for various wind conditions, partly based on creating a neutral helm. Some sailors like to rake the mast further forward in heavy air to reduce weather helm. If you want more weather helm, say in light air, rake the mast further back.

#3. Board angle and depth

In a boat with pivoting boards, raising the board moves the CLR aft, reducing weather helm. Many tuning guides suggest raising the boards in heavy air. World class dinghy sailors even try to momentarily raise the centerboard in puffs. Besides moving the CLR aft, raising the boards also reduces their surface area. This lets the boat sideslip slightly more to absorb the side force of the wind.

In boats with daggerboards (no pivot), pulling up the daggerboard also moves the CLR aft, since the decreased surface area reduces the board’s overall effect on the CLR.

#4. Fore and aft weight placement

According to several sources we reviewed, moving crew forward moves the CLR forward, increasing weather helm. However, when we tried this in our MC scow, we found just the opposite effect. We concluded that in our light-weight scow, we also pitched the boat forward, moving the CE further forward than the CLR.

Regardless of the effect on of fore and aft weight placement on helm balance in any specific boat, there are better reasons to move crew weight fore and aft, such as keeping the bow attached to the water in light air, and keeping the bow out of the water in waves.

#5. Sail power and shape

As the wind picks up, the increased sail power creates additional weather helm for several reasons:

- If you let the boat heel up, you’ll create weather helm.

- Even if you control heel, the increased wind strength amplifies the effect of any slight misalignment between the COE and CLR.

- The sails change shape with increased wind. The position of maximum draft shifts aft, moving the COE aft and thus creating weather helm. Compensate by flattening the sail with the vang/mainsheet and pulling the draft forward with the cunningham. See our post on Draft Shape and Position for more.

- More twist in the sail moves the COE forward and reduces helm.

#6. Boom angle

If you let the boom out by easing the mainsheet or moving the traveler to leeward, the aft portion of the sail moves to leeward and forward, which also moves the COE forward. This reduces weather helm. Many sailors adjust their traveler based on helm feel.

Using Helm Balance – Situations

As you become more aware of helm balance, you’ll find an increasing number of situations that require you to actively manage it. Here are several examples.

Accelerating from a standstill

Ever notice how difficult it is to accelerate from a standstill when you are almost head to wind? If you bear off slightly and slowly trim in your sails, the aft portion of the sail fills in first, creating weather helm that heads you back into the wind. The problem is that you need to bear off to fill your sails, but you also need speed to make your rudder effective against the initial weather helm. The key is to bear off far enough and then trim your sails quickly so that the whole sail fills.

Choosing angle of heel

In most boats, sailing at the proper angle of heel is critical for good performance. Since angle of heel affects helm balance, it makes sense get the angle of heel right first, and then adjust helm balance. In Striking a Balanced Helm (Sailing World), Mike Ingham discusses the interplay between angle of heel and helm balance. Here are a few examples.

- Some keelboats need heel to increase the righting moment of the keel. Thus they accept a little weather helm.

- Some boats sail better in chop with a slight angle of heel. If so, they make other helm balance adjustments and often accept a little weather helm.

- Scows are designed to sail with 10-15 degrees of heel. The best scow sailors adjust to get a nearly neutral helm at that optimum angle of heel.

Sailing by feel upwind

With a very slight weather helm (3-5 degrees rudder angle), you can often sense changes in the wind by feeling the pressure on the tiller. This lets you react quickly without looking at the sails or telltales. telltales. Here are some examples:

- Puffs. In a puff, your first reaction is to control the angle of heel by having your controls on (before the puff!), and then easing the sail and hiking. If the puff is substantial, you’ll still feel more weather helm, even if you keep the heel angle constant. If so, “feather up” by letting your tiller hand move to leeward to follow the excess pressure. Stop when the helm pressure returns to normal and before it diminishes below normal.

- Lifts. In a lift, you also may get slightly more helm pressure, but this won’t likely be as much of an increase as in a puff. Since the helm pressure change may be slight, you will need to use other clues, such as shroud telltales or the ripples on the water to confirm a lift.

- Lulls. In a lull, helm pressure will decrease and the boat will flatten. Your first reaction should be to get controls off (before the lull!) and get your weight in to maintain constant heel. Resist the temptation to bear off to establish helm feel! It’s the lighter wind, not your heading that causes the decrease in helm pressure. For more, see our post Sailing Lulls, Part 2.

- Headers. In a header, helm pressure will decrease as the sail luffs. Confirm the direction change with your shroud telltales and your sense that the wind speed has not changed. Then bear off to re-establish helm feel.

Flat water/steady wind

In these conditions you can get by with less weather helm by trimming your sail flatter. With a flatter sail you’ll point better, but you’ll have a narrower groove and less helm feel, so you need to be on your toes.

Waves/gusty wind

In these conditions, you’ll be steering actively and want a rounder sail entry for a wider groove. A little weather helm will help you feel the changes. However, too much weather helm will make steering down difficult.

Other SailZing posts on Weather Helm

Weather Helm vs Lee Helm – What is it? How to Use it? – Nautic Ed

Sail Faster with Less Hiking – Part 2: Sail Setup ILCA website – good discussion of tuning for weather helm

Balance Your Helm for Speed – johnellsworth.com